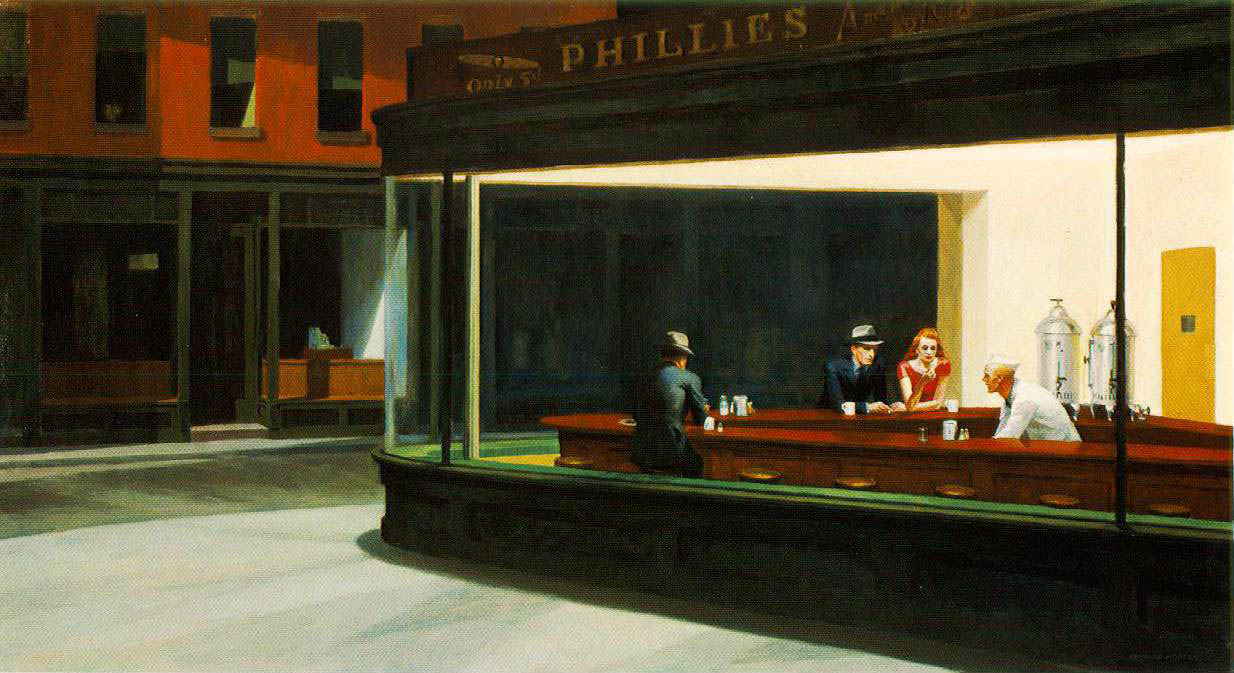

National Gallery of Art/Associated Press Caravaggio's "Taking of Christ," painted in 1602 and misplaced after nearly four centuries; the figure holding a lantern at right is thought to be Caravaggio himself.

By BRUCE HANDY

The New York Times

November 13, 2005

Historians take windows where they can find them, and in certain circles this entry from a 17th-century ledger bears particularly vivid witness: On Jan. 2, 1603, a Roman nobleman named Ciriaco Mattei paid 125 scudi - the liras of the day - for what his bookkeeper described as "a painting with its frame of Christ taken in the garden." The artist in question, Michelangelo Merisi, known to most of us as Caravaggio (after his hometown outside Milan), was then among the most famous, innovative and copied painters in Rome - the Picasso of his day, more or less. But tastes change, and the realism that was bracing and revelatory to his contemporaries left a bad odor in the 18th and 19th centuries. By the turn of the last one Caravaggio had become but a footnote in art history. And so, another window: on April 16, 1921, according to the notation on a catalog from a now defunct auction house, "The Taking of Christ," misattributed at the time to a minor Dutch painter, was sold at auction in Edinburgh, for a mere eight guineas, a silk purse pawned off as a pig's ear.

Roger Viollet/Getty Images

And then, of course, the wheel turned again: today, the dirty feet of Caravaggio's models don't distract us from his formal beauty - gosh, we're inured to Nan Goldin - and we live in an age when anyone with a Metropolitan Museum of Art wall calendar will instantly recognize Caravaggio's mature style, gorgeous and stark with its dramatic angled lighting, deeply shadowed backgrounds - did Caravaggio invent film noir? - and muscular, often contorted figures. Fold in the fact that (a) he lived a short and violent life (he was known to the police, as they say, eventually fleeing Rome after killing a man in a fight over a gambling debt), and (b) it's hard to miss the homoeroticism of so much of his work, and you have all the ingredients for a 21st-century museum superstar. Indeed, the painter's current renown is such that Jonathan Harr has gone to the trouble of writing what will probably be a best seller on the subjects of what has happened to "The Taking of Christ" since 1603 and who has cared enough to find that out.

To Caravaggio scholars, whose discipline became academically viable when the artist's reputation rebounded in the 1950's, "The Taking of Christ" was a famously vanished work, known only through copies made by the artist's followers. Harr's rich and wonderful book, "The Lost Painting," is an account of how, in 1990, the original was found. I'm tempted to quick-key a cliché and say the book reads like a thriller, because it's as gripping as a good one and even kicks off with the ritual opening: a brief prologue suggesting the high stakes of the game afoot, followed by the introduction of an unlikely and unprepossessing but, in the end, surprisingly resourceful heroine. She is Francesca Cappelletti, a 24-year-old graduate student in art history at the University of Rome who is about to stumble upon Something Really Really Big.

In truth, the book reads better than a thriller because, unlike a lot of best-selling non-fiction authors who write in a more or less novelistic vein (Harr's previous book, "A Civil Action," was made into a John Travolta movie), Harr doesn't plump up his tale. He almost never foreshadows, doesn't implausibly reconstruct entire conversations and rarely throws in litanies of clearly conjectured or imagined details just for color's sake, though he does betray one small weakness in this regard: whenever his subjects are out and about, the sun always seems to be slanting low across the rooftops of Rome or bathing the church domes of the city in a golden light while the swallows of spring circle and pirouette overhead. On the other hand, if you're a sucker for Rome, and for dusk, you'll forgive these rote if poetic contrivances and enjoy Harr's more clearly reported details about life in the city, as when - one of my favorite moments in the whole book - Francesca and another young colleague try to calm their nerves before a crucial meeting with a forbidding professor by eating gelato. And who wouldn't in Italy? The pleasures of travelogue here are incidental but not inconsiderable.

The foreground pleasures are those of a police procedural. In order to gain access to the archives of a noble Roman family, Francesca chats up a dotty old marchesa using all the cunning of a Columbo snuffling around for an inadvertent clue. It is in that archive, while researching the provenance of another Caravaggio painting (a young, nude and flirty John the Baptist with his arm around an interested ram), that she and her colleague, Laura Testa, discover the 1603 ledger entry, which becomes the first important signpost leading to the identification of "The Taking of Christ." As the players in this drama multiply - and given the career stakes, everyone involved seems remarkably decent; the book could have used a good villain - we are treated to an art historian's version of "C.S.I." Canvases are X-rayed and scanned with infrared light, paint surfaces are examined for telltale traces of the painter's M.O. - the way Caravaggio, who didn't work from preparatory sketches, scored the ground of his paintings with the nonbusiness end of his brush to work out his compositions. Terms such as craquelure - an old painting's characteristic "web of fine capillary-like cracks" - are tossed around. As with any version of "C.S.I.," there is even a decent yuck moment here during a sequence in which the book's second main character, an art restorer named Sergio Benedetti, mixes up a pot of glue with eye-of-newt ingredients: "a quantity of pellets of colla forte made with rabbit-skin glue, an equal quantity of water, a tablespoon of white vinegar, a pungent drop of purified ox bile." Harr notes that Benedetti prefers this recipe to another calling for an entire ox skull.

The author has a wonderful ability to bring this sort of tradecraft to life. For instance, there is this description of another restorer, Andrew O'Connor, cleaning the surface of a filthy painting:

"He used cotton swabs and began with distilled water, barely dampening the swab, to remove the superficial dirt. Occasionally he wet a swab in his mouth. Saliva contains enzymes and is often effective at removing dirt and some oils. In Italy he'd seen restorers clean paintings with small pellets of fresh bread. The process of cleaning old paintings has a long history, not all of it illustrious. In previous eras, paintings had been variously scrubbed with soap and water, caustic soda, wood ash and lye; many had been damaged irreparably. An older restorer once described paintings to O'Connor as breathing, half-organic entities. 'It's a good thing they can't cry,' this restorer said, 'otherwise you would go to museums and have to put your fingers in your ears.' "

It is this empathy for the passions of these scholars and artisans, Harr's respect for their dedication and his keen understanding of their workaday worlds - he clearly spent a lot of time with his subjects - that elevates "The Lost Painting" into something more provocative than just your average missing-Caravaggio narrative. A good thing, too, since the timing and circumstances of the discovery of "The Taking of Christ" deflate much of the book's suspense; halfway through, it's all over but the backfilling. Fortunately, the hunt for the canvas is a bit of a MacGuffin; the deeper mystery is the nature of capital-A art itself. In that vein, early in the book, Harr offers a sketch of Sir Denis Mahon, the greatest living expert on Caravaggio:

"Sir Denis believed that a painting was like a window back into time, that with meticulous study he could peer into a work by Caravaggio and observe that moment, 400 years ago, when the artist was in his studio, studying the model before him, mixing colors on his palette, putting brush to canvas. Sir Denis believed that by studying the work of an artist he could penetrate the depths of that man's mind. In the case of Caravaggio, it was the mind of a genius. A murderer and a madman, perhaps, but certainly a genius."

Windows on history, windows on men. Ledger entries and masterpieces, both with their "tells." So what does "The Taking of Christ" reveal about Caravaggio? It is one of the artist's most intimate religious paintings - a tight medium shot in Hollywood terms, the action filling the frame with a choreographed immediacy Michael Bey must admire if he's ever seen it. Jesus, off center, calmly accepts his fate, hands clasped, gaze downcast. Judas has just kissed him, the apostle's face inches from his master's, his left hand still gripping Jesus' shoulder, the two locked in a complicated embrace of love and betrayal while a pair of Roman soldiers move in - the decisive moment, in Cartier-Bresson's term. And on the far right Caravaggio has painted himself, raising a lantern: the artist symbolically illuminating the scene. But left hanging, as many critics have pointed out, is the question of Caravaggio's literal role in the scene: mere bystander or member of the arresting party? Is he faithfully illustrating God's design or implicating himself in Judas's treachery? Caravaggio frequently painted himself into his works, often behind a patina of self-loathing, at least to post-Freudian eyes. (In perhaps the most dramatic example, a painting of the victorious young David, he used himself as the model for Goliath's severed head, a look of nauseated despair on his face as his blood drains from his severed neck.) It is this conflicted quality that roils so many of his paintings of martyrdoms and miracles; he may have intended his high-beam lighting to dramatize God's divine love and judgment, but coupled with the dark backgrounds and deep shadows, the effect, as in "The Taking of Christ," can also be isolating, each figure swaddled in its own gloom. These are literally dark nights of the soul - Christianity, before the advent of feel-good megachurches, was full of them - and that's one reason the artist speaks so powerfully to modern audiences: three centuries before Munch, Caravaggio had found a visual language for dread.

So, yes, certainly a genius, and an attractively tortured one at that, though Harr records Benedetti's observation that Judas's left arm is too short, a clumsy error of perspective on Caravaggio's part: "It looks like he painted the shoulder and then didn't have enough room for the arm." Of course: nobody's perfect. Maybe Caravaggio was hurried. Maybe he was lazy. Maybe he didn't notice. But it is that teasing interplay between craft and inspiration, between a painting's physicality and its import, between what is knowable about art and what, ultimately, is not, that resonates throughout "The Lost Painting" and underscores a satisfyingly ironic coda: In 1997, seven years after it had been painstakingly restored, its provenance documented, and its place rightly restored among Caravaggio's canon, "The Taking of Christ" was discovered to be infested with biscuit beetles, a common household pest, which were feeding on all that rabbit-skin ox-bile glue that had been used to repair it. Despite the heroic efforts recounted here, ashes-to-ashes can hold true, it seems, for paintings as well as their painters. There's beauty in that, too.