Jeremiah Moss

July 2, 2010

The New York Times

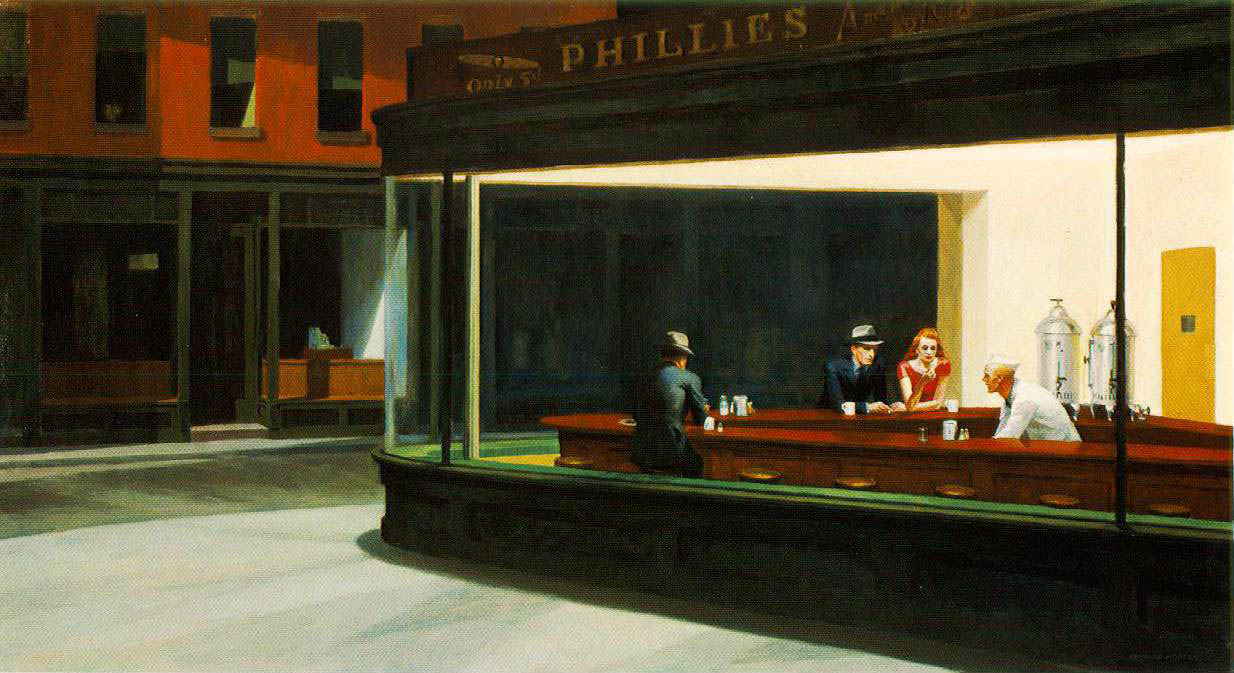

Not long ago, one of the readers of my blog, Vanishing New York, sent in an old photo of the lot. There was no diner, only an Esso gas station and a White Tower burger joint that looked nothing like the moody, curved, wedge-shaped lunch counter in “Nighthawks.” An urban mystery had just revealed itself: If the diner wasn’t in the empty lot, then where was it? Being an obsessive type, prone to delve, I began searching for Hopper’s diner with the help of two of my readers. Multiple streets converge at Mulry Square, creating a shattered-glass array of triangular corners. The buildings wedge themselves into these tight angles, bricks tapering to near points, each structure bearing a Hopperesque resemblance. I snapped photos of every possibility and checked them against their ancestral images in the New York Public Library’s Digital Gallery. I made a trip to the city’s Municipal Archives, where I scanned the 1930s atlases of Manhattan known as “land books,” matched block and lot numbers to scratchy rolls of microfilm and scrolled through muddy 1940s tax photos. Slowly, I began ruling out suspects. The empty lot at Mulry Square held a gas station from at least the ’30s through the ’70s, not a diner. I had to rule out the buildings on nearby corners of the square as well: West Village Florist was a newsstand. Fantasy World was a liquor store. Two Boots Pizza, with its lovely prow wrapped in rounded glass and chrome, was the Hanscom Bake Shop. And the pie-slice of a luncheonette that stood behind the lost Loew’s Sheridan cinema was too blocky, too brick-y to be the elegant diner in the painting.

So I expanded my search, looking at nearly every curvilinear corner where “two streets meet” off Greenwich Avenue. With each rejected candidate, my hopes of finding the “Nighthawks” diner fell. After hours of hunting the archives, I was about to give up when I found a new clue in a 1950s land book. There in the map of Mulry Square, not in the empty northern lot, but on the southwest side, where Perry Street slants, the mapmaker has written in all caps a single revelatory word: DINER. I went into a state of panicky thrill. Sometime between the late ’30s and the early ’50s, a new diner appeared near Mulry Square. This was it. I could smell the coffee brewing. After decoding the block and lot number, written in script so small it required a Sherlockian magnifying glass, after retrieving the microfilm spool and scrolling to the specified location, I discovered ... nothing. The tax photo showed only that old Esso station. I scrolled back and forth to be sure, but found no photo of the southwest corner, no photo of the diner in question. Did the tax photographers forget to take its picture? Did they mislabel the lot? It’s possible that I started muttering out loud to myself in the quiet of the Municipal Archives, because people began to stare.

Back home, I dug through my bookshelves and unearthed Gail Levin’s “Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography.” The book is autographed by the author — I had gone to hear Ms. Levin read in a bookshop that is now gone — and dated from a time when I was still new to the city and knew it largely, romantically, as a sprawling Hopper painting filled with golden, melancholy light. In the book, Ms. Levin reported that an interviewer wrote that the diner was “based partly on an all-night coffee stand Hopper saw on Greenwich Avenue ... ‘only more so,’” and that Hopper himself said: “I simplified the scene a great deal and made the restaurant bigger. Unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city.” Partly. More so. Simplified. The hidden truth became clearer. The diner began to fade. And then I saw it — on every triangular corner, in the candy shop’s cornice and the newsstand’s advertisement for 5-cent cigars, in the bakery’s curved window and the liquor store’s ghostly wedge, in the dark bricks that loom in the background of every Village street. Over the past years, I’ve watched bakeries, luncheonettes, cobbler shops and much more come tumbling down at an alarming rate, making space for condos and office towers. Now the discovery that the “Nighthawks” diner never existed, except as a collage inside Hopper’s imagination, feels like yet another terrible demolition, though no bricks have fallen. It seems the longer you live in New York, the more you love a city that has vanished. For those of us well versed in the art of loving what is lost, it’s an easy leap to missing something that was never really there.

No comments:

Post a Comment